I Love You I Know Art

On March 10, 1914, a woman entered the National Gallery in London, strode upward to Diego Velázquez's Venus at her Toilet, (ca. 1647–51) and began hacking at the masterpiece with a meat cleaver. The woman was Mary Richardson, a suffragist who pronounced the attack an act of protest against the imprisonment of Emmeline Pankhurst, the famed women'south suffrage leader, who had been arrested the previous solar day. "I have tried to destroy the picture of the near beautiful woman in mythological history," Richardson boldly asserted. By the fourth dimension she was accosted, the famously sensual painting, which shows a recumbent nude Venus seen from behind, had been slashed seven times (it was ultimately successfully restored).

Colloquially known every bit the Rokeby Venus, the painting was considered by many to be the superlative of European beauty. The Spanish Golden Age masterpiece had come up to England in 1813, when it was brought to hang in Rokeby Park, Yorkshire. Over the course of the century, it had go one of the most treasured paintings in England: when the canvas was sold from Rokeby Park in 1906, a public campaign raised an astonishing sum of£forty,000 to purchase the painting for the National Gallery.

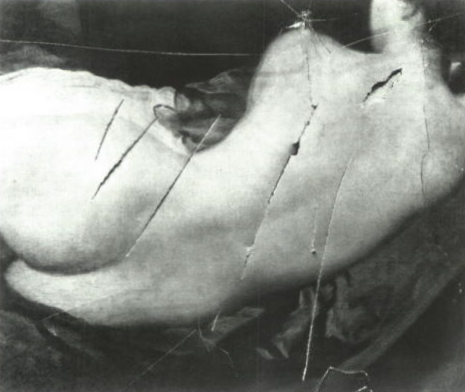

Photograph of the damage from the attack by Mary Richardson in 1914. The tears were subsequently restored.

For the famed field of study of the painting, that was a bit ironic: The Toilet of Venus had been kept entirely out of public view for more 150 years after its cosmos, seen only past a small circumvolve of male person elites. Famously, it is Diego Velázquez's but surviving nude (others, known through records, have been lost); the painting was made during the Inquisition in Kingdom of spain, when nudes were strictly (and punishably) forbidden. Yet, Spanish courtiers still nerveless these pictures avidly, largely from abroad—and Velázquez, as the court painter of Rex Philip IV, was afforded certain liberties.

It is believed that Velázquez completed his Venus on one of his visits to Italian republic, inspired by masterpieces of both the Renaissance and antiquity, including Giorgione'south Sleeping Venus (ca. 1510) and the ancient sculpture Sleeping Hermaphroditus (which was then in Rome), of which the creative person commissioned a downscaled version and sent it back to Kingdom of spain.

While it is unknown for whom, exactly, this Venus was painted, it was held in the collection of several Spanish nobles, including that of the famed libertine Gaspar Méndez de Haro, 7th Marquis of Carpio, who was notorious for two passions: women and fine art. The u pheavals of the Napoleonic Wars ultimately brought the painting to England.

Sleeping Hermaphroditus, an ancient Roman copy of a Hellenistic original, excavated ca. 1608–20 and now in the Louvre.

Unknown in its era, The Toilet of Venus would prove greatly influential to the likes of Édouard Manet and Pablo Picasso centuries later. Today the Rokeby Venus, every bit it is known, is one of the most iconic images of the Castilian Gilded Age.

Then much intrigue surrounding a painting tin can cloud our perception of it. This Valentine's Day, we've taken a closer look at "the well-nigh beautiful woman in mythological history" and unearthed 3 fascinating details that just may make yous see her in a whole new light.

Venus Stripped Bare (and Brunette, Too)

Peter Paul Rubens, Venus at a Mirror (ca. 1615).

In many senses, Velázquez'south Toilet of Venusturned convention on its caput. The motif of the goddess caught mid primp had a long and storied history, with Titian, Veronese, and Peter Paul Rubens all making versions. The iconography for these scenes more often than not entails a nude Venus seated, looking at herself in a mirror, and adorning herself with jewels and ointments in a boudoir of groovy refinement. What's more than, she is almost always is blonde.

Velázquez's approach is starkly modern, even austere. Firstly, his bending is highly unusual; he finer combines two traditional compositional strategies for portraying Venus—the recumbent Venus and Venus looking at herself in the mirror. The depiction of Venus from backside was an erotic device in antiquity; the reference to the Sleeping Hermaphroditus Velázquez saw in Italy is credible).

Velázquez'due south Venus is a brunette, and the mythological paraphernalia associated with the goddess—jewelry, roses, and myrtle—are all absent-minded. Rather than a room of nifty splendor, this Venus appears in an artist'south studio, with carmine drapes pinned against a bare wall and a black sheet (a incomparably Spanish bear upon), seeming to shadow the line of her silhouette atop a couch or mattress. Instead of the voluptuousness of, say, Rubens's Venus, here we run across a slender more gimmicky woman (k uch has been speculated virtually the artist's unknown model, with some believing her to be his mistress, since nude female models were prohibited).

Cupid, too, has been pulled into reality. He appears non as the jolly and mischievous god of myth, only as a little boy, his wings solitary providing a tip-off that this is a scene from myth. In fact, in early inventories, the painting is described every bit mujer desnuda, or nude woman, rather than by its mythological discipline matter.

Rather than jewels, where Velázquez lavishes care and particular is the body of Venus, which gleams like a pearl, the brushstrokes all but invisible. The composition is virtually photographic in effect, with the trunk in focus and the rest of the scene blurred out. Everywhere else, Velázquez's mitt is loose, brushy, and suggestive—Cupid'south face up is merely hinted at, as are the pink ribbons hanging on the mirror (perchance meant to exist the fetters with which Cupid spring lovers). This stripping-down of conventional elements had one intended upshot: playing up the painting's existent-life eroticism.

Velázquez's Trick Mirror

Detail of the Rokeby Venus (ca. 1647–51), past Diego Velázquez.

One of the pleasures of this painting is its ambiguity, a trip the light fantastic toe between revealing and concealing. Drawn outset to Venus'southward trunk, the heart wanders up toward the blush of pink on her cheekbone. We want to run across her face, and that wish seems to exist granted as our eyes move to the rectangle of mirror, which holds her reflection. Except Velázquez withholds; he has blurred his Venus's mirrored visage, offering merely the suggestion of a adult female's face, and leaving the details of her likeness to our imaginations.

Simon Vouet, The Toilet of Venus (ca. 1640). Courtesy of Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh.

Another wait at that reflection reveals one more mirror trick. Venus appears to be looking at herself in the mirror, but simultaneously we perceive her to be looking directly at us, the viewers. The perspective is incommunicable and notwithstanding perceived coherently. This perceptual phenomenon is, in fact, known as the "Venus event" for its prevalence in paintings of the goddess of love, and speaks to a psychological state of affairs in which people concur beliefs that differ from appreciable reality.

It May Take Been Painted to Be a Pendant

Richard Cooper, Venus Reclining in a Mural. Copy of a Painting Formerly Attributed to Giovanni Antonio da Pordenone(undated). Drove of the National Galleries of Scotland.

What is most anomalous about the Rokeby Venus is her unusual positioning; she is both recumbent and turned away from the viewer. The compositional strategy creates a sculptural upshot that seems to urge the viewer to walk around to run across her other side.

Inquiry sheds new light on this novel arroyo, with documents suggesting that Velázquez's painting was intended equally a pendant for a mysteriousVenus of Pordenone—a recumbent Venus in a landscape that shows a nude female effigy in the same pose as the Rokeby Venus, merely from the front. William Buchanan, the art dealer who brought the painting to England in 1813, lists the work as a pendant. In the 1750s, Scottish artist Richard Cooper fabricated an annotation on the back of his fatigued copy of Velázquez'due south Venus, maxim "Venus and Cupid'. Velázquez. Large equally life. In the collection of the Duke of Alva, Madrid. (Velázquez painted this as a companion to the Venus of Pordenone.)" Cooper had also made a pencil cartoon of the Venus of Pordenone.

The trail of the Venus of Pordenone went cold afterward a 1925 sale, merely the painting seems to accept been rediscovered by English dealer Alex Wengraf in 1994, according to scholars Enriqueta Harris and Duncan Bull (Wengraf appeared with the painting on the idiot box program "The Private Life of a Masterpiece: The Rokeby Venus by Diego Velazquez"; run across infinitesimal 23:00.).

"[N]ot but is the motif of a reclining nude resting her head confronting her right paw in itself unusual for this type of full-length field of study, but the contours of the two bodies, the disposition of their legs, the angles at which their feet are placed, and the manner in which both tuck their right heels beneath their left calves, all suggest that one of the pictures was painted with straight knowledge of the other," write Bull and Harris in the essay "The Companion of Velázquez's Rokeby Venus and a Source for Goya's Naked Maja."

Francisco Goya, The Naked Maja (ca. 1797–1800). Drove of the Museo Nacional del Prado.

Whether or not Velázquez painted The Toilet of Venus in response to Venus of Pordenone, what is substantiated by records is that the paintings were both in the collection of Gaspar Méndez de Haro and were displayed side by side for many years. The pair were then sold together, entering the collection of the Duke and Duchess of Alba, and later that of Manuel de Godoy, who hung the two paintings alongside Francisco Goya's infamous duoThe Naked Maja and The Clothed Maja, probable commissioned past Godoy—and which themselves may have been partially inspired by the Venus of Pordenone.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to go the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

rotherbehienceeten51.blogspot.com

Source: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/diego-velazquez-rokeby-venus-facts-2069892

0 Response to "I Love You I Know Art"

Post a Comment